Story

Story Vol.17

A Work from the Final Phase of Exploring the Diverse Possibilities of Modern Clock Design

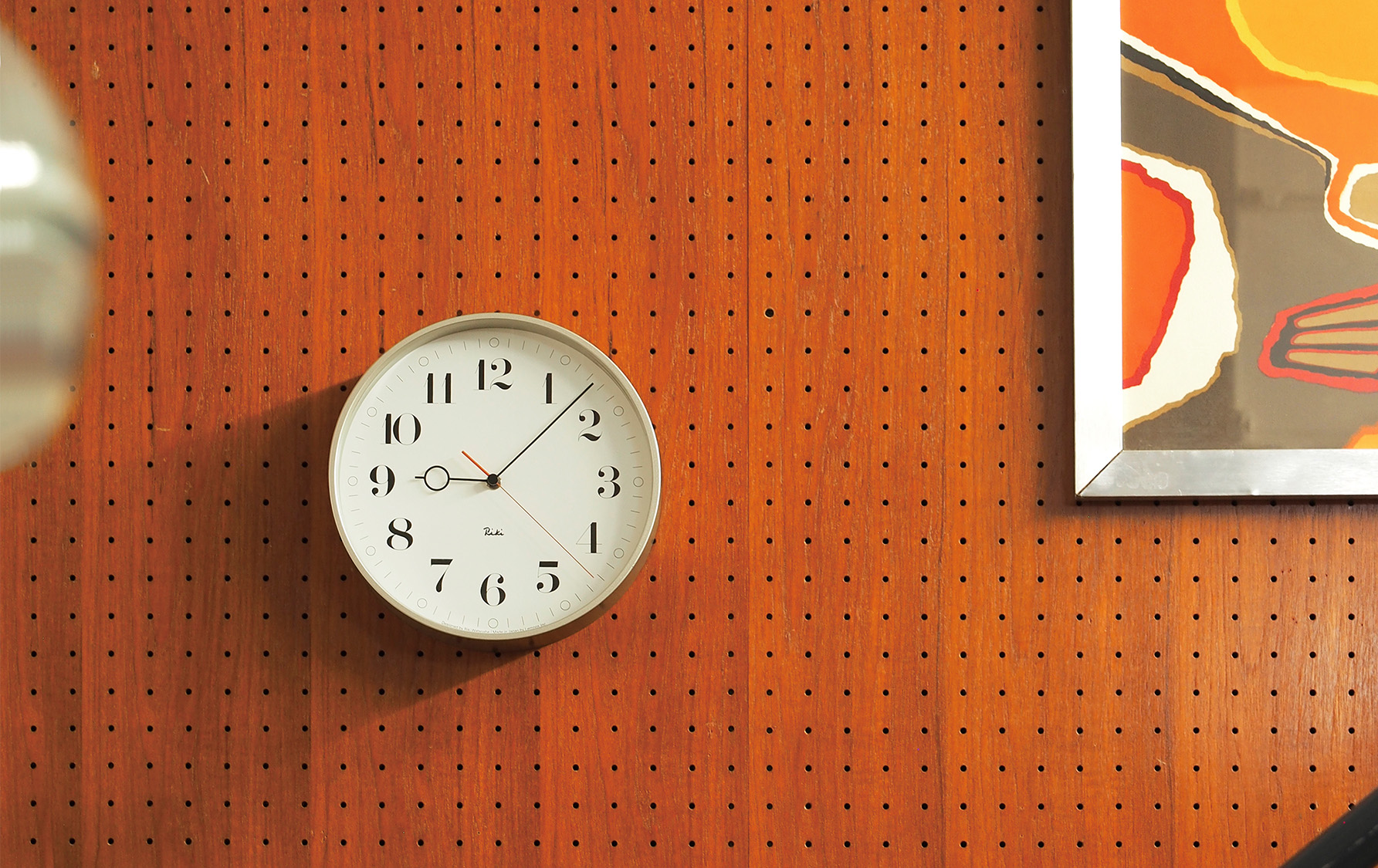

This is a reissue of the RING CLOCK by Riki Watanabe, originally released in 1981. Watanabe pioneered the field of personal clocks with designs that were simple, unpretentious, and highly original, yet faithful to the fundamentals of clockmaking, with legibility as the foremost priority. From the late 1960s to the early 1980s, he played a leading role in shaping the dawn of Japan’s modern clock era.

[ Text: Akira Yamamoto ]

We spoke with Akira Yamamoto about the RIKI RING CLOCK, which received the 2021 Good Design Award in recognition of its effort to preserve and convey beauty that transcends simple modernism.

Left: Riki Watanabe / Right: Akira Yamamoto

A 1981 Design from the Final Phase Before Stepping Away from the World of “Design Clocks”

After designing mass-produced clocks since the 1960s, Watanabe stepped back from the field and turned his attention to one-of-a-kind works (e.g., public clocks and personal experiments) until he returned to watch design in 2000. The RING CLOCK, designed in 1981, belongs to that final phase. It was a time when Japan was moving from a period of rapid economic growth to the bubble era, and design was shifting from modernism to postmodernism. Within this changing landscape, the clock quietly reflects Watanabe’s attitude, which neither resisted the spirit of the times nor wavered from his own principles.

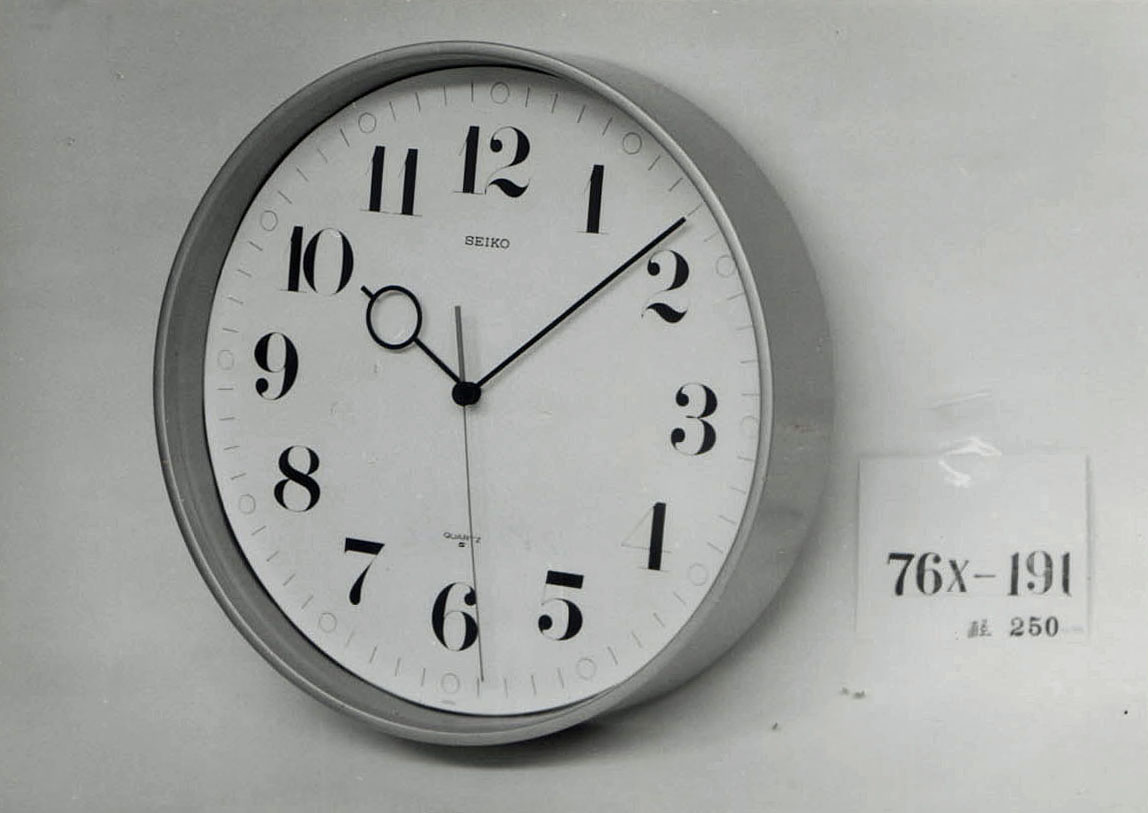

We knew about this clock since the early days of our collaboration with Watanabe. However, we were so captivated by the bold simplicity of the RIKI CLOCK that this model appeared somewhat incomplete in the catalog photos, as if it lacked a certain presence. Over the years, as we gradually redesigned and reissued Watanabe’s classic works (e.g., the Small Wall Clock and the Steel Clock), our understanding of clock design and Watanabe’s creations became increasingly refined. For instance, take Hibiya no Tokei. Although it is one of Watanabe’s most iconic works, it was originally created for public spaces, and its commanding presence made it seem too imposing for indoor use. As a result, commercialization was not initially considered. Then one day, someone suggested, “Maybe it could work?” and the entire team soon embraced the idea. Its eventual success followed the same process; through firsthand experience with Watanabe’s series of works, we gradually came to recognize and appreciate the true essence of his design.

There is no record of Watanabe ever commenting on this clock. Although he designed countless interiors and products, many were never even photographed—except for a few that he felt particularly attached to. His reasoning was simple: “Once something is released into the world, I can only see its flaws, and I’m left with nothing but regret over what I could have done better.” It is possible that the RING CLOCK was an experimental piece, or one overshadowed by his more confident works, such as the Small Wall Clock, which introduced the innovative idea of the personal clock, or the RIKI CLOCK, which showcased his pioneering use of Arabic numerals in clock design.

The Culmination of Pursuing the Diverse Possibilities of Modern Clocks

So, how should we interpret the RING CLOCK? Perhaps it represents a culmination that was reached after Watanabe explored the full range of possibilities in modern clock design. It conveys a release from the taut, meticulously refined tension of his earlier works, leaving a lingering, airy lightness. The transitional period from the formality of modern design to the rise of postmodernism surely influenced this shift. There may also have been a conscious effort on Watanabe’s part to bring everything together before stepping away from the world of clockmaking.

Signature “Glasses” Hands and Circular Markers: Balancing Legibility and Symbolic Simplicity

The Arabic numerals use Watanabe’s iconic CBS typeface, which is rendered here with a stronger contrast in line weight than his other clocks. Their balanced placement lends the design a refined, almost delicate impression, rather than a bold statement. The hour hand adopts the decorative “glasses” style, which was first used in his debut analog clock, a custom wall clock created for Wako. Watanabe continued to explore this motif in several unrealized prototypes, which suggests a personal attachment to this form. In harmony with the “glasses” hand, the dial features circular hour markers that echo its shape. For Watanabe, legibility always came first in clock design, followed by the beauty that emerges when simplicity is refined to its limit. Many of his clocks feature hands and markers with deliberately contrasting thickness and length for this very reason. While the “glasses” hand and circular hour markers may at first appear playful or unconventional, they are in fact rooted in his core principles: enhancing the distinction between hours and minutes, while expressing clear, symbolic simplicity.

Recreating the Original Character with Millimeter-Perfect Numeral Placement and Sub-Millimeter Line Refinements

When we were fortunate enough to acquire an original of this clock, we expected the reissue to go smoothly. The faithfully reproduced dial and hands were assembled and compared with the original, yet something still felt off. We spent considerable time studying the differences, adjusting details (e.g., the bold–thin contrasts in the CBS numerals), and fine-tuning line thickness, lengths, and proportions by less than 0.1 millimeters. Still, the unique character of the original did not fully emerge. In the original, the dial logo featured the manufacturer’s name at the top center, while the reissue replaced it with “RIKI” at the bottom. To unify the series identity, we also added product credits along the outer ring, which slightly widened the dial’s outer margin. Even though the numerals, hour and minute markers, etc., matched the original in size and placement, the overall impression of the clock inevitably changed. From there, the process became a long journey, guided by the intuition that we developed through years of studying Watanabe’s clocks. Each adjustment was made by eye, taking care to preserve that immediate sense of identicalness at first glance. The clock’s simplicity leaves nowhere to hide. It’s a delicate, deeply expressive object, and even the slightest imperfection becomes visible. We also re-engineered the frame structure by replacing the steel press-molded construction with a more rigid aluminum casting. This change added a pleasing sense of depth and a premium quality to the clock, while allowing our group company to manage production and ensure stable manufacturing.

RING CLOCK: A Refined Balance of Decoration and Function with an Airy Lightness Contrasting the Bold Presence of the RIKI CLOCK

Watanabe’s rigorous approach to clock design allowed him to establish the “design clock” as a distinct genre, and there is no doubt that his series of works stand as masterpieces of Japanese modern design. We believe that in the field of clocks—where functionality has already reached a high level of maturity—the most accessible way to experience good design is not by preserving discontinued masterpieces solely in museums or private collections; it is by continuing to produce and sell them so that they can be used widely, as part of everyday life. This approach has been well-received by the market and embraced with high regard, which shows that it functions as a living, practical form of archive. While the RIKI CLOCK is known for its bold presence, the RING CLOCK stands in striking contrast, with an airy lightness and a beautifully refined balance between decorative elements and pure functionality. It goes beyond simple modernism to serve as a model for the next generation and as an important work that deserves to be carried forward into the future.

A Clock Frame Crafted with Takata Factory’s Advanced Aluminum Casting Technology

Since the release of the original in 1981, manufacturing technology has advanced significantly. Clock movements have become smaller and about half as thick as before, which made thinner clock designs the mainstream today. However, for this reissue, we intentionally retained the original clock’s balanced depth and volume to convey a sense of premium quality and enhance the product’s overall appeal. The original pressed-steel frame was surprisingly prone to deformation. To address this, we redesigned the structure and took advantage of our group company Takata Factory’s advanced aluminum casting technology. The result retains the frame’s distinctive form while improving rigidity, thus simplifying assembly and making handling easier during shipping and user installation. Furthermore, this collaboration enabled stable supply and precise production control, while minimizing waste during manufacturing and disposal.

This revision of the manufacturing process was undertaken to enhance the product’s appeal and ensure its continued production and availability for many years to come.

Riki Watanabe

(1911–2013) Graduated from the Woodwork Department of Tokyo High Polytechnic School. After working as an assistant professor at Tokyo High Polytechnic School and as an assistant in the Forestry Department at Tokyo Imperial University (the existing Tokyo University), he established Japan’s first design office, the RIKI WATANABE Design Office, in 1949. His main focus was the establishment of the Interior Architect Department at Tokyo Molding University, Craft Center Japan, Japan Industrial Designer Association and Japan Designers Committee. He designed the interior decor at the Keio Plaza Hotel, Prince Hotel, etc. and furniture such as the “Himo-Isu (Rope chair)” and “Trii-stool”. Moreover, from wall clocks and watches to a public clock called “Hibiya pole clock” at Dai-ichi Life Holdings in Hibiya district, his work on clocks and watches became his lifework. He received the Milano Triennale Gold Medal in 1957, the Mainichi Industrial Design Prize, Shiju hosho(the Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon), and many other awards/recognitions. In 2006, the “Riki Watanabe – Innovation of Living Design” exhibition was held at the National Museum of Modern Art.